A year or so ago, I had an exchange with the United Daughter of the Confederacy about the monument to CSA General Edmund Kirby-Smith on the campus of the University of the South in Sewanee, TN, where I teach. My proposal was to hire an artist to make an installation to sit in front of the monument to draw attention and enter into a sort of artistic dialogue with it. The UDC didn’t like my idea but, as I never formally suggested it to the administration, nothing came of it. Frankly, it seemed like a pipe-dream that anything could happen with the monument.

Since that time, a lot has happened. Trump has become President and extreme right-wing movements have been emboldened. During the summer, a large protest of Neo-Nazis marching together with the KKK took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, and a protester was killed by them. The rallying point for the alt-right demonstrators was a statue of Robert E. Lee. In the wake of Heather Hayer’s death, communities across the nation began to reconsider the purpose of their monuments honoring of the Confederate cause. The mayor of Baltimore ordered all Confederate statues taken down in single night. Protesters in Durham, NC, took matters into their own hands and, like people in Eastern Europe after the fall of Stalin, pulled another such statue down from its pedestal themselves.

Locally, interest was renewed in our own Confederate memorial in light of these events. The Sewanee Slavery Project, headed up Woody Register and Tanner Potts, held a forum to discuss the monument, and all such signs of the Lost Cause dotting the campus. The day before, the Vice Chancellor sent out an e-mail indicating that, at the request of one of the Kirby-Smith family, the monument was to be relocated to the University Cemetery, presumably by the general’s grave.

As it happened, I had wanted to get the feeling of some of the Kirby-Smith family living in town, and was talking with one of them when the e-mail came out. I know he felt left out of the conversation–the cousin who had made the request lives in another state–but acknowledged that, had he or any of his local relatives been consulted, they would probably have agreed to the moving of the monument to their great grandfather. Not that their feelings about the matter were determinative, but still it might have made sense to have consulted them. For the sake of the family, some of whom I consider close friends, I am happy to see the monument removed and to see this particular burden lifted from them.

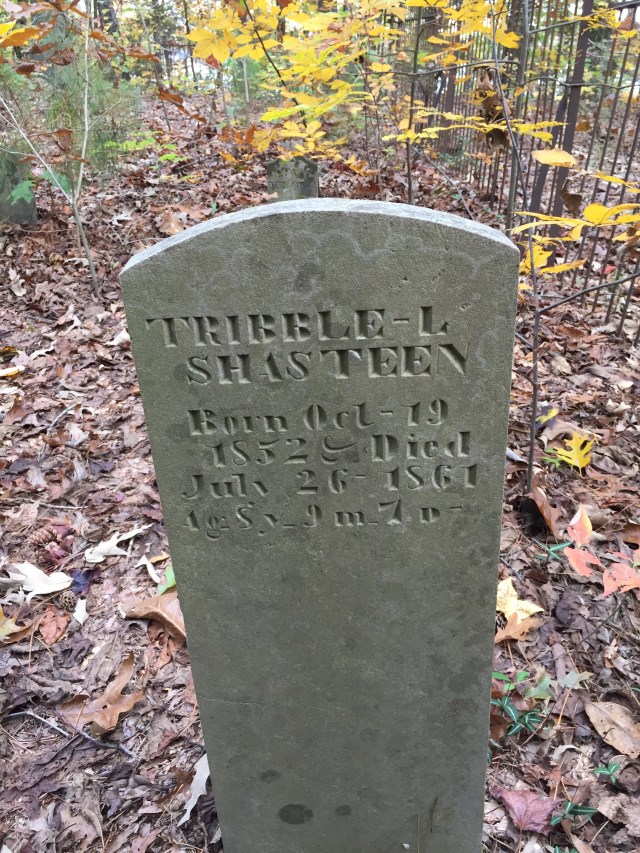

In any event, the Vice Chancellor made his decision a month or so ago, and time has marched on. The leaves have changed, the weather has gotten cold, and soon we will turn back the clocks. It was only a matter of time, I knew, before I would walk by the monument and see–or rather, not see–the General’s visage in bas-relief on its plinth there on University Avenue. The sandstone all around has grown dark and discolored, but the spot where the medallion was affixed is still the bright yellowish-brown it was back in the 1940s when the monument was dedicated. The letters of the general’s name have not been removed, or at least not yet. Soon, I suspect they and the plinth itself will be gone as well.

Speaking for myself, I wish it would remain in the very place where it is right now, and in the very condition of my photo up above. The Romans had a term for this (or rather, they had the concept, to which classicists have given the term), damnatio memoriae, “the condemnation of memory.” The process did not involve the removing of all traces of a disgraced public figure, but rather removing the name and image in such a way that they could still be made out. The point was not to consign the figures in question to oblivion once and for all, but rather to consign them to oblivion every single time one came across their oddly missing presence.

And I wish the same would happen to the general, to the cause he fought for, and to the organization that put up this memorial. I would like it if, every time we walked down University Avenue, we saw his ghostly absence on the street, and remembered that once, on this spot, it was OK to honor those who fought a brutal war to keep others enslaved. It’s all too easy to decide the past is past, that it has nothing to do with us, and to let it all go down the memory hole. And then, one pleasant summer day, there’s a neo-fascist torchlight parade in a university town and somebody gets mowed down by a car. Evidently, amnesia isn’t a viable solution to our national ills concerning racism. To forget the disgraceful reasons the Civil War took place, and the disgraceful people who fought for it, is not enough. We must always remember to forget them, and to remember why we are doing so.

* Quite a few people, some of whom I admire, have taken issue with my line “and the disgraceful people who fought for it,” so I’ve decided to give it a little damnatio memoriae of its own. I’m still torn on this, to be honest. Disgraceful causes don’t do the fighting for themselves, after all. But then I think of the even-handedness with which Homer treats both the Greeks and the Trojans, perhaps possible only because it is a fictional war without real-world consequences.

This summer I read Plato’s Laches and parts of the Protagoras on courage–I was especially interested to know whether it is possible to be noble in the service of ignoble causes? Could we honor Confederates for their gallantry, even if we had to condemn their ideology? I don’t think Socrates ever really sorts the issue out, but if all virtues are part of one great Truth, he thinks it’s not possible for any of them to ultimately be at odds with one another.

In the end, I suspect that name-calling is not especially virtuous itself. There’s something about motes and beams in another ancient text that I recall.

An evening or two ago, I stopped into Mooney’s, the great little local market just on the border between Sewanee and Monteagle, to pick up some garlic powder. I had paid for it, when it occurred to me that I should grab one of those delicious chocolate bars they sell as well–grabbing one, I laid it on the counter though the garlic powder had already been rung up.

An evening or two ago, I stopped into Mooney’s, the great little local market just on the border between Sewanee and Monteagle, to pick up some garlic powder. I had paid for it, when it occurred to me that I should grab one of those delicious chocolate bars they sell as well–grabbing one, I laid it on the counter though the garlic powder had already been rung up.